Mattis Molde, Neue Internationale 289, February 2025

The global auto industry is in upheaval. Global corporations are fighting each other for sales, supported by the major powers with which they are linked. Just how thin the line is between market supremacy and decline is shown by the example of Volkswagen (VW), the group with the highest turnover to date. However, VW is not the only company affected by the crisis in the industry; all others must also reposition themselves in the face of tougher competition.

The background against which this car war is taking place is the global economic crisis itself and the resulting struggle for the redivision of the world by the major imperialist powers. Events on the car market and in the car industry are linked to this – all the more so when the respective national economy is based on the car industry and there is no country for which that is more true than for Germany.

The situation for the established manufacturers from Europe, the USA, South Korea and Japan is as follows:

- An enormous over-accumulation of capital is facing a divided market that is overflowing with cars. The tendency for the average rate of profit to fall has exacerbated this situation, since less and less profit can be made from each car. One of the ways in which this is being addressed is by increasing the output of cars.

- Different Chinese manufacturers are entering the global car market with production costs that are around 30% lower. So far, they have expanded to a major degree in their own domestic market, which is the most important car market in the world, but in the next period they will also gain a stronger foothold in Western markets and especially in semi-colonial countries.

- For the established manufacturers, the car war means having to destroy surplus capital, for example, through plant closures, mergers and takeovers and to push down the relatively high wage costs in their long established centres with attacks on wages, relocation of production to semi-colonies.

- Technological innovations secure only a short-term competitive advantage for individual corporations and thus short-term extra surplus value for them. However, as soon as these innovations are generalised, the average profit rate falls as a result of a higher organic composition of capital. This also leads to models being renewed more quickly, partly due to the technological race, partly due to political measures like scrappage schemes or subsidies that lead to existing cars being replaced more quickly. All of this serves to secure billions in profits – not to the best possible reduction of emissions in the fight against the climate crisis.

For the working class, the auto war means that it is being waged on their backs and they will pay for it if no international united resistance by auto workers is developed – not only because of the brutal competition between corporations, but also because plants and locations within a corporation are played off against one another. Such resistance must also raise the question: What should be produced, especially in the face of the climate crisis? Millions and millions of cars or, for example, buses and trains for a socially useful mobility, for which, moreover, much less work would have to be done? The question is also: Who owns the factories, who controls them, who decides on these huge productive forces?

Upheaval since 2000

Let us first outline the situation. The automotive industry is globalised through the division of labour in manufacturing. The same applies to the highly competitive sales markets.

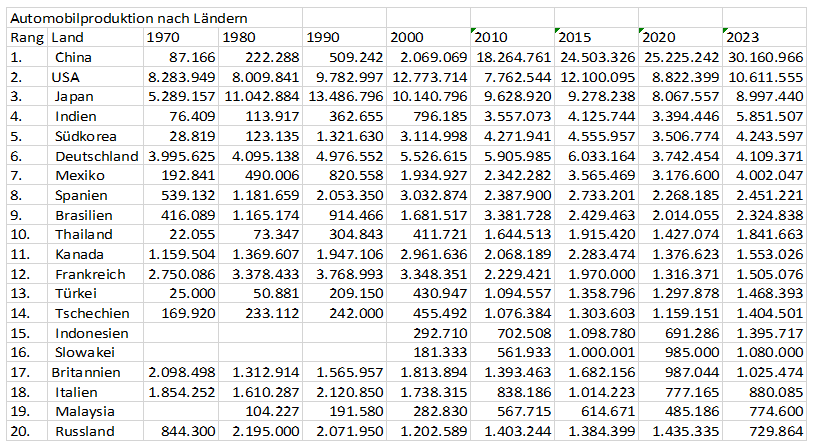

Until 2000, car production was concentrated in the US, Europe and Japan. Since then, the centre of the global automotive industry has shifted to mainland Asia. Overall, the number of cars produced annually rose by a good 60% by 2023. But virtually all of the growth took place in Asia, and particularly in China. In 2023, almost 60% of all motor vehicles were built in Asia and almost 50% were sold there.

Two historical events lie behind this. China, under the leadership of the Communist Party, was transformed from a degenerate workers‘ state into a capitalist country, where production was again carried out for profit and state property became capital, seeking to increase through the exploitation of labour. This development also forced China to face competition on the world markets and to take a position in the imperialist power structure.

Secondly, the capitalist restoration in China and the former Soviet Union triggered a process known as “globalisation”: the inclusion of all countries and markets in a new division of labour with the aim of increasing profit rates by using cheaper labour. For the former bureaucratic workers‘ states in Eastern Europe, this process meant that existing industry was partially bought up, but for the most part it was closed down. New “extended workbenches” of international corporations emerged there.

The increasing rationalisation and automation of production also required ever greater investment in production and assembly facilities. This development has encouraged the emergence of even larger and stronger corporations and has also intensified competition among them. The larger investments must preferably also pay for themselves quickly, so that production must take place around the clock if possible. In addition, the lifespan – the so-called “lifecycle” – of the models has been significantly shortened, so that the need for investment has increased here as well. There is less leeway to slowly phase out a model when demand declines. Instead, it must be replaced as quickly as possible by a new model that promises high unit sales. Against the backdrop of stagnating sales figures, which have been observed for about 4–5 years, this is an additional factor that further intensifies competition.

At the same time, the automotive markets have lost much of their national character. Many models are produced for a global market, with national adaptations if necessary.

All of this has encouraged the emergence of even larger and stronger corporations. Many old and well-known companies have been swallowed up or merged. Chrysler, Rover, FIAT, Lancia, Peugeot, Citroen, Volvo and Porsche have since ceased to exist as separate companies and now live on only as brand names. Conversely, the end manufacturers (OEMs, Original Equipment Manufacturers) have outsourced the production of parts and sold them. This has also led to the emergence of large global supplier corporations (parts production) and many other smaller and larger suppliers that depend on the large corporations.

These processes have permanently changed the markets and the production structures – and, of course, the car companies themselves. A representation of the development of global car production shows this shift towards Asia, as well as the emergence of new, and the decline of old, production countries.

However, this conceals different developments. This shows a presentation of the ten largest groups by turnover.

While Germany has slipped from third place (in 2000) to sixth place (in 2023) as a production location in terms of the number of cars, three German companies dominate the top 10 in terms of turnover – more than from any other country. This is due to the fact that turnover per car varies greatly. General Motors, for example, generates only slightly more turnover than BMW, but builds more than twice as many vehicles. The most expensive cars are predominantly built by the German companies.

On the other hand, it is clear that the three German groups VW, Mercedes and BMW sold over 14 million vehicles in 2023, but only a good four million were produced in Germany itself (Table 1). Of the four million cars produced in Germany, some were also manufactured by companies based in other countries, such as Ford, Stellantis (Opel) and Tesla. There is currently only one company from China in the top 10 (SAIC), but this will change significantly in the coming years.

German corporations

In its study „The automotive industry in 2024”, the German Economic Institute makes clear the distinction between the location of production and that of its corporate headquarters when it describes the approach of German corporations in the development after 2000:

“Between 2000 and 2017, production in Germany grew significantly. The basis for this was the special business model of the German automotive industry. This was based on two pillars: active globalization of production and sales on the one hand and dominance in the premium segment on the other. This strategy made it possible to manufacture and export high-priced vehicles in Germany for the global market. In fact, a good 75 percent of the cars built in Germany in 2023 were exported, around 40 percent of them intercontinentally. But this successful business model has begun to falter.“

This study also describes how the proportion of vehicles manufactured in Germany had already fallen below 50% of all units built by the German automotive industry by 2009. In 2018, China became the most important production location. And: “In 2023, the share of vehicles manufactured by the German car companies in Germany was slightly less than 30 percent.”

In addition to the strong shift to China since 2005, production in Eastern Europe also grew by around 800,000 units. In the USA, production by the German automotive industry increased by 600,000 units, but has stagnated since 2016: “All in all, the German automotive industry still manufactures a good 50 percent of its vehicles in Europe, while the rest is produced on other continents.”

This study also presents impressive figures for the cars sold in Germany by VW, BMW and Mercedes: „The domestic market accounts for between 12 and 13 percent of the units sold by the three manufacturer groups. In 2010, it was still up to 23 percent. The sales share of Europe excluding Germany also fell visibly between 2010 and 2023. It remained relatively constant for the Volkswagen Group, while the decline for the BMW Group amounted to almost ten percentage points.“

But: „The most important single market for all German manufacturer groups is China. Here, the sales share in 2023 was between 32.4 and 36.4 percent. The importance of business in China developed very differently between 2010 and 2023. The Volkswagen Group, which has been active in China since the early 1980s, already reported a sales share of almost 32% for China in 2010. This rose to almost 40 percent in 2019 and has been declining since then. In contrast, the two manufacturer groups focused on premium vehicles have seen a continuous and significant increase in sales in China. For BMW and Mercedes-Benz, China accounted for around 12% of total sales in 2010. This share rose to around 33 percent for BMW and 36 percent for Mercedes in 2023.“

But China is not everything. „These two manufacturer groups also have a relatively high share of sales in the USA. This is around twice as high as for the Volkswagen Group. In view of the special nature of the North American vehicle market, this strong position in the US market is probably mainly due to large SUVs, which BMW and Mercedes produce in the USA for the global market and also export from there to Europe. In this way, BMW has become the largest car exporter in the USA.“

SUVs, which are still perceived in Germany as more of an American phenomenon, are actually a German market and export hit: „At the turn of the millennium, the German car industry had virtually no SUVs on offer, but in 2023 they accounted for almost 47 percent of total production. This development was driven primarily by the USA and China, where the SUV share of new registrations is once again significantly higher than in Europe. The share of SUVs in new registrations in China in 2023 was around 50 percent – in Germany it was closer to 30 percent. The SUV boom was responsible for the majority of production growth in the German car industry, which amounted to a good 200% between 1981 and 2023.“

Electrification

The IW study dispels the myth that the “powertrain turnaround”, that is, the switch to electric cars, has caused difficulties for the German automotive industry: „Focusing production on larger vehicles and thus achieving dominance in the global premium segment was a key prerequisite for the economic success that the production figures of the German manufacturer groups have enjoyed since the millennium. In fact, the premium strategy is also proving to be helpful in the ongoing technological shift towards electrified powertrains, as customers in the premium segment traditionally have a greater willingness to pay for new technologies. It has therefore always been standard practice in the automotive industry for new technologies to be introduced in the luxury class first and then find their way into the lower vehicle segments via falling unit costs.“

However, this also proves that it was not the threat of a climate catastrophe, but the usual hunt for profit that drove this changeover.

The German companies‘ difficulties are only just beginning because „the high-margin premium segment is also attractive for new manufacturers specializing in electric vehicles. In China, it can be observed that such new manufacturers have begun to attack the market position of the German automotive industry. They have already achieved success in the important Chinese market. The Volkswagen Group’s declining sales in China are attributable to such new competitors. The share of Chinese brands in total sales in China rose from 40 percent in 2020 to 65 percent in the first half of 2024. This development is being driven by electric cars manufactured in China. The German automotive industry’s global market share for electric vehicles is around 15 percent – slightly less than its share of the overall market.“

Imperialism

What the study is cautious about is political intervention. It concentrates on lamenting the introduction of tariffs, especially those that would affect exports from Germany or exports of German companies. However, in view of the fact that the latter also export heavily from the USA or China, the Economic Institute sings the song of free trade loudly and refrains from calling for tariffs on cars from non-German companies, for example.

It remains silent about the fact that the countries in which car companies are based do everything they can to support this globally important industry. In other words, without the power of a leading imperialist country behind them, it has been impossible to survive in the global car war in recent decades. Weaker imperialist countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden and Spain, but also stronger ones such as Britain, have lost their car manufacturers. On its way to becoming a world power, China has also been able to, and had to, build up a car industry – after all, the car business is one of the most profitable in the world.

It is elementary for understanding imperialism in general, but also German imperialism in particular, that a transfer of value from the semi-colonial world to the imperialist centres takes place through global production chains. This means that the profit also ends up in Germany. VW also pays the comparatively high wages here from extra profits, which are exploited by production in other countries. In the next period, however, this will become too expensive for the VW-Group, hence the latest major attack.

The measures used to support these global monopolies include enormous subsidies as well as technical trade restrictions and tariffs – and the power to enforce them. Not even weaker imperialist powers have this power, let alone semi-colonies. Even the EU will have difficulties countering Trump’s announced US tariffs with something similar.

The US rescued General Motors in 2009 by temporarily nationalising it and spending $51 billion after its debts had more than doubled the value of the company. The high Chinese subsidies are cited by the EU Commission, the media and many others as justification for tariff barriers.

The fact that China’s e-car export wave does not conceal exuberance, but stagnation, is revealed by a statement in the Financial Times on March 26, 2024: „However, the growth of China’s electric car industry, which now accounts for more than 30 percent of domestic passenger car sales, has masked the breathtaking decline in non-electric car sales. Last year, 17.7 million cars with internal combustion engines were produced in China for the domestic market, down 37 percent from 28.3 million in 2017.“

German subsidies are also incredibly high and hide under many titles: The three car companies grab the lion’s share of research funding, and they receive billions more for powertrain electrification and digitalisation. The short-time working funds during the 2009 crisis and the coronavirus crisis went mainly to this industry. The tax privilege for company cars in Germany is also a direct subsidy for the car industry. In addition, there are infrastructure projects that are also subsidised with state or municipal funds, land development, freeway connections, parking spaces, etc.

The prime-ministers of the “car states” of Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg and Lower Saxony have just called for the billions in fines that the car industry faces according to EU-regulation if it exceeds the CO2 limits to be “suspended”. For example Winfried Kretschmann (the Greens minister-president for Baden-Württemberg since 2011), said that the climate targets were not being called into question. “Instead, the industry, which has long since moved towards climate neutrality, is being given the necessary flexibility.” This is total denial of reality, as traffic emissions in Germany continue to rise, not fall, but is a continuation of a policy that has also failed to hold corporations accountable for emissions fraud with diesel engines!

Finally, we can also mention the Agenda 2010[i] measures, which have led to a massive expansion of temporary work, the internal division of the workforce and lower wages in the car industry. The “special business model” of the German car companies has therefore not spread across the country like a blessing from the corporate headquarters in Stuttgart, Munich and Wolfsburg, but has been paid for by employees in Germany with wage losses. In addition, colleagues in France, Italy and the UK have bled for the German export surplus with massive job losses. From 2000 to 2023, production figures fell by 64% in France, 62% in Italy and 45% in the UK.

From this point of view, the social partnership of IG Metall union and the works councils in the automotive industry is not just about collusion with management. It also serves German capital to represent and enforce the interests of global corporations against competition from other monopolies. Social partnership is therefore one of the most important levers of German imperialism to increase industrial exports and the surpluses generated in the process compared to the competition. It is not far from the “car war” of national locations to the support for rearmament, arms exports and the war policy of one’s own country, which IG Metall openly pursues today – IG Metall by the way also organises the workforces in German arms factories.

Class war against car war

A comprehensive analysis of the situation in the global car industry shows that many assessments are completely wrong, failing to distinguish between Germany as a car production location and the German car monopolies. Jacobin writes: “The German car industry can no longer be saved”, apparently without realising that some of the cheap Chinese cars that will soon flood European markets will be built by VW. Of course, the profit will still end up in Wolfsburg, from where it will be distributed to the pockets of shareholders all over the world.

Nevertheless, it is of course clear that the Chinese manufacturers themselves will also storm the European car market and expand into it. It doesn’t help the German car industry much that many customers in the country have a fetish for German brands (although these cars themselves have gone through a global production chain and are by no means the result of “German workmanship”).

The German model since 2000 is now at an end. The intensified conflicts between the imperialist blocs of the USA, China and the EU make it highly unlikely that Europe and Germany will be able to provide a disproportionate share of the international car monopolies. If the global crisis then causes car production to stagnate – and in the case of Europe even a shrinking market – then it becomes clear that these are all just expensive rearguard actions. It is far more difficult to conquer other fields here than to secure new shares in a growing market.

Growth and stabilisation of the big three can no longer be achieved by producing lots of big, expensive SUVs in Germany. The sacrifices that IG Metall and the works council at VW have now agreed to will only lead to more sacrifices, but will not save anything. Just as little will further subsidies, such as those demanded by IG Metall, Chancellor Scholz, the car state premiers and the companies themselves, keep car jobs in Germany. The laws of capitalism are stronger. The German car industry must respond to China by making production cheaper – and that means relocating production to countries with lower wage costs or launching massive attacks on the working class here.

What is playing an ever less important role in the public debate today – six years after the emergence of Fridays for Future – is the role of the car industry in the climate crisis. Here, too, the laws of capitalism will dominate. Where the debate is still being conducted, it still revolves primarily around the question of the powertrain, even in left-wing circles. Here, too, the potential answer lies with the workers of the car industry themselves.

Let us therefore outline the battle that needs to be won:

- The climate crisis requires a transformation of production towards other products such as functional low weight e-cars (instead of SUVs) as well as buses and trains or other products that are actually socially necessary.

- As enormous industrial capacities exist, these products – which are also not required to the same extent as cars are churned out today – can be manufactured with a fraction of today’s working time.

- This saving in working time points to a general reduction in working time and a distribution of work among all. While today the increase in productivity leads to profit maximisation and job cuts, it is important to make it the starting point for much, much more free time.

- Even less radical proposals put forward in the debate about the car, traffic and jobs immediately provoke massive resistance from the monopolies, the bourgeois states and the bourgeois parties – it not only jeopardises their car war, which they want to win, but also raises the question of social control.

- As a result, their car war must be transformed into a fight against the car companies by the workers themselves. For every job, for every plant – and for a completely different system of production – a democratic one, planned according to the needs of the population.

- Such a transformation will only happen on the basis of the expropriation of these corporations and the building of workers‘ power against the bourgeois states. To achieve this, the class that can break the power of these corporations must be won over – for us, the struggle for a revolutionary workers‘ party is also on the agenda here.

The struggles for this can start with the defensive battles against plant closures, but they must always be linked to transitional demands that lead to the conquest of power. This will only be possible if these struggles are waged in an internationalist manner from the outset. Otherwise, the auto worker class of one plant, of one country, along with our livelihoods, will be sacrificed on the auto battlefield – ostensibly for jobs or prosperity at home but, in reality, only for future billions in profits.

Note

[i] Agenda 2010 was the name of a programme of social cuts and “reforms” applied by Chancellor Schröder to set the EU-Lisbon-Agenda into practice in Germany. Now the likely future Chancellor, Friedrich Mertz, promises an “Agenda 2030”.